ONE PANDEMIC, TOO MANY CONFUSIONS

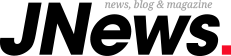

The conflicts over data and information access, the «dynamic plateaus», the confusing or inaccurate reports that have had to be remade, the COVID card, mall openings, the «new normality» and lockdown parties, are all signs clearly showing that the government has failed to communicate and summon Chileans across the nation to overcome this disaster.

This is directly detrimental to the most primary objective of any government facing a crisis of these proportions: to build a shared strategy, to convene, and unite everyone to carry it out. Unfortunately, the current situation is different. There is a feeling that both the experiences of countries that previously faced coronavirus do not apply to the Chilean context for some reason. Neither the scientific evidence accumulated so far applies. The government feels overly confident, while the experience indicates that this health crisis must be tackled decisively and pragmatically, but also with caution and humbleness.

What to do? Facing a situation that is far from easing and requires a greater joint effort to get out of it, a review of what decades of disaster risk management (DRM) research and practice have taught about governance and crisis communication can help. If there is one thing that experiences in DRM have been able to establish, it is that natural or biological events cannot be separated from the social, economic and political dimensions of a society.

For this reason, a crisis can be an opportunity to amend the conditions that made it possible or help deepen pre-existing conflicts, even creating new ones. Chile is going through a moment of social movements demanding to be doubly careful, both in the forms and in the substance of the actions and messages that authorities must design. What DRM teaches us is that health management in a context such as the current one cannot be solely health-related: it must always be conceived in terms of the socio-political conditions of each society and striving to create a democratic climate of unity and collaboration.

Based on the lessons learned from centuries of socio-natural disasters, and in light of the research we have developed at the Research Center for Integrated Disaster Risk Management, there are at least six reflections that we believe could help us improve in the difficult stages ahead:

ONE, AND ONLY ONE STRATEGY

British sociologists John Law and Vicky Singleton say that the challenge of disasters is not a lack of sense, but an excess of sense: too much information, too many solutions, too many experts. This is why, when facing a crisis, the authorities must establish and explain the objectives of the strategy to be followed, drawing a path which, being nonlinear, must be understood and maintained over time. Moreover, if that path cannot be traced or kept, then it must be recognized by explaining the due reasons. Unfortunately, what we have seen in this period has been quite different.

Every week the government has surprised us with new strategies, new concepts or definitions, and even worse, new ways of accounting for health statistics. How can we change the course? One key that emerges from the literature on DRGs is to seek collaboration and coordination with different agents: science, communities, businesses, social organizations, NGOs, etc. By coordinating the different expertise and sensibilities through a transparent mechanism, the route mapped out will gain legitimacy and a minimum of sustainability.

-

TRIUMPHALISM IS A BAD ADVISOR

If we could anticipate disasters or know how they will develop, they would not be disasters.

That is why, dealing with the unknown, governments must always nourish their analyses and actions with caution and humbleness, something that has been conspicuous by its absence during these two months of crisis. Instead of accepting the «unknown unknowns» of the situation and choose a precautionary principle, the official discourse has preferred complacency, where comparisons Chile is always «top ten» abound.

This type of message to the population, which must rather encompass the difficulties endured by the established formal systems to support them in a disaster context, thus assuming an active role in the designed solutions, cannot be worse. The defiant and «winning» attitude in which there is no doubt or fragility inspires a sense of normality that can be lethal in a disaster context, and even more in a pandemic whose peak is uncertain and unknown.

-

NARRATIVE MATTERS

Language creating reality is a maxim that takes on special importance in disaster situations. It should be remembered that disasters are times when, as Kay Erikson says, the «we» is blurred, which means that the complete stability of social life is challenged. That is why we must look for communication manners that help to recover a sense of community. The war vocabulary/language used by the government points precisely in the opposite direction. First, it assumes that there is an enemy when it is the human actions and the socio-material conditions that they have built what should take the blame to overcome a disaster. Secondly, it presents the pandemic as a warlike and shocking issue, when in disaster situations the energy of the communities, on the contrary, is focused on look after affections, relationships, and what is common.

MEANS FOR DIALOGUE

The role of the media in how a crisis is reported becomes fundamental to successful DRM. Neither the media nor communication can solve problems that are rooted in —and respond to— structural political processes, but they can help mitigate them. That is why the role of the media in building compelling narratives and clear strategies is key. According to some experts, crisis communication could be addressed as a tool for simply transmitting data; the role of the media then would be to disclose information from official sources to people and hopefully have the population follow the instructions designed by the state. But as Robert Cox suggests, communication can also be an agent that plays a role in creating the meaning of the crisis, enabling a process of dialogue between different actors. Unfortunately, Chilean media have mostly chosen the first model. Besides, in several cases they have stooped to painful stigmatizations (for example of the migrant population) or into unnecessary centralists perspectives, preventing the development of common sense to handle the crisis.

LOCAL DISASTER RISK MANAGEMENT

A key lesson in DRM theory and practice is the importance of the local level throughout the disaster cycle. It is there, in/on territories and communities, that any action must finally be deployed and where the situated knowledge to make that deployment fit local realities resides. That is why the tension between the government and the municipalities has been a bad sign. Without finding government support or the will to understand territorial challenges, many municipalities have chosen to deploy their interventions autonomously. Working together with municipalities and territorial groups would have been a powerful signal to citizens, which could have helped to raise confidence and reduce uncertainty.

THE IMPORTANCE OF (COLLABORATIVE AND CITIZEN) SCIENCE

For DRM, a critical challenge is to define the science role and to define the relationship between science and citizens. And as Andrew Lakoff points out, the challenges are many. On the one hand, governments must make decisions based on evidence, but in a transparently and without forgetting political and social considerations. On the other hand, governments must be able to explain clearly and openly the scientific basis of their decisions: this is not only a condition in democratic societies but also a requirement for the population to recover in disaster situations, which Anthony Giddens calls «ontological safety». The problems with data delivery —including the crisis of the “data board”— and the citizen unrest over dynamic quarantines and their capricious spatial segmentation are examples of the difficulties the Chilean government has had in articulating an open, transparent and collaborative platform to strengthen the State-science-citizen relationship in light of the huge needs out of certainty in unstable times.

DECONFINEMENT AND RECONSTRUCTION

We believe that the government is in time to correct the problems we have addressed. The experience gained when facing earthquakes, tsunamis, floods or fires should be considered to draw a new communication and relationship strategy among critical agents. It would be a crucial step for the government to build a broad and shared vision that considers the complex dimensions at stake. In times of disaster, form, and substance are equally relevant and key not only to effective crisis management but also to prepare what will come next: the lack of confidence will bring challenges in the areas of mobility, education, public spaces, and work, not to mention the imminent risk of new outbreaks, the inevitable economic recession and the context of the constitutional plebiscite in October. It would be unforgivable to come out of the pandemic with an even more broken political and social coexistence than the one we had when we entered it.

This article was published in CIPER Academic (Journalistic Research Center online platform) by Rodrigo Cienfuegos, Manuel Tironi, and Karla Palma.